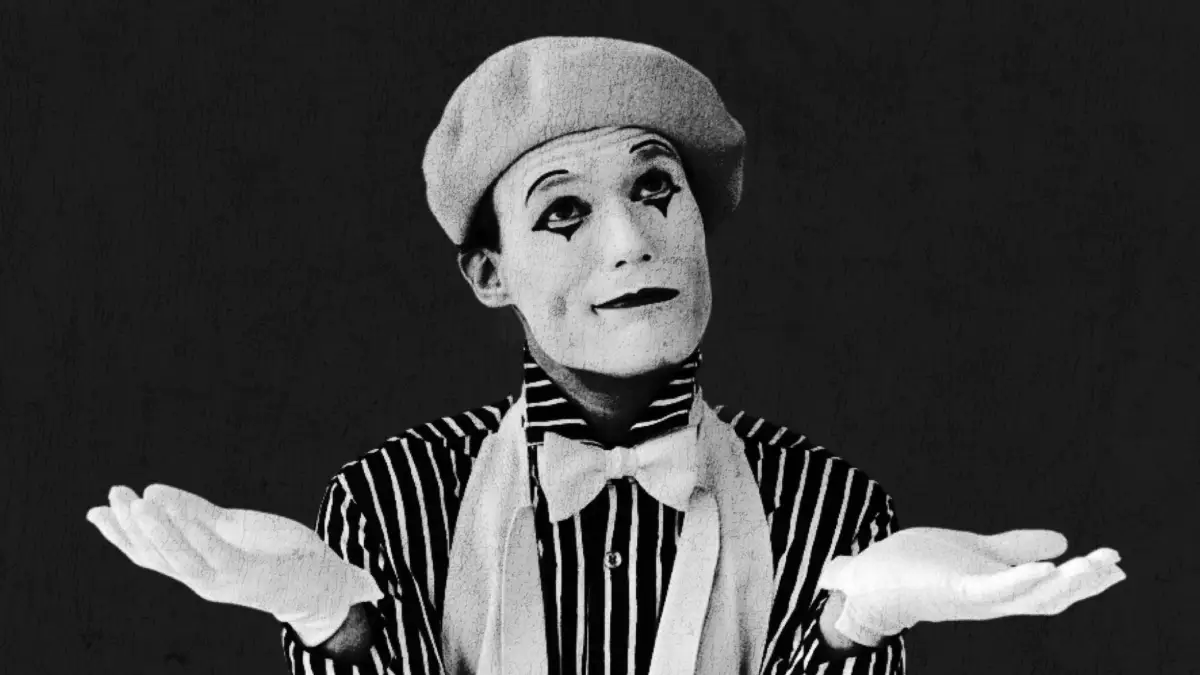

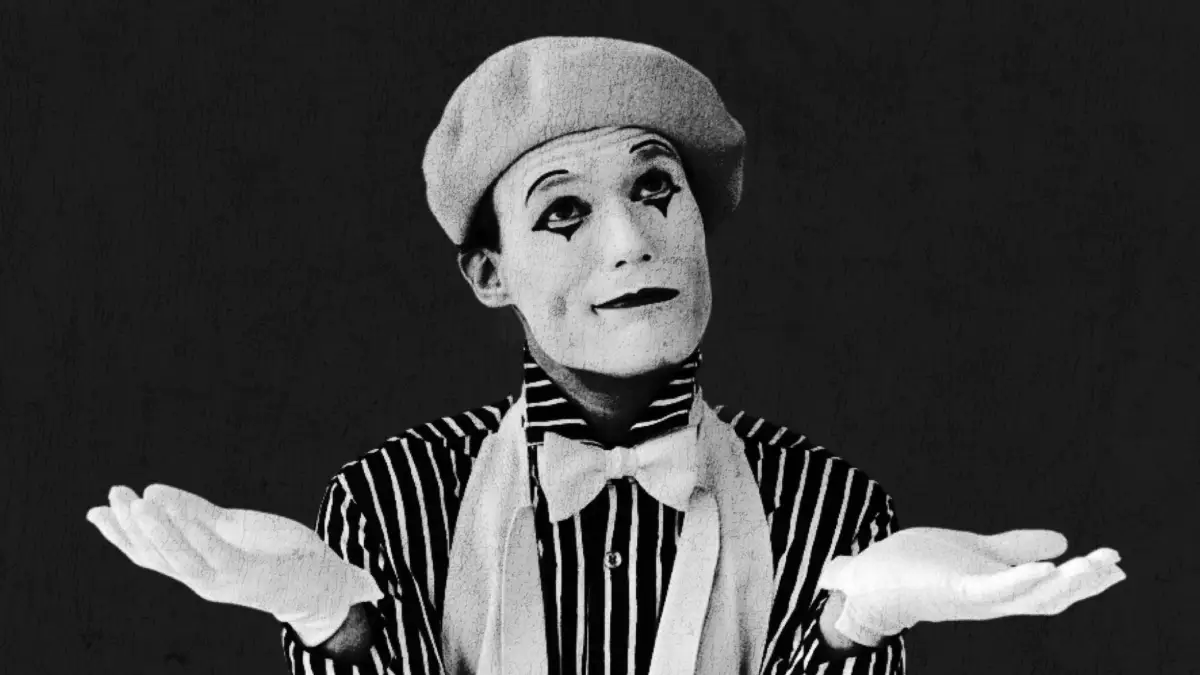

Mocking, missteps and maintenance nightmares

Mocking has a reputation problem. But is it just misunderstood? Misused? Or simply… mis-titled?

Two camps, both alike in dignity

Mocking has become a cornerstone of unit testing, but as with many things in software, it is far from universally loved. It has its share of vocal proponents and wary detractors.

In one corner, the enthusiasts advocate for design clarity driven by fast, isolated tests. In the other, sceptics complain of overcomplicated tests that break by the dozen with every refactoring.

Both are not wrong - mocks can help engineers design better software, but they can also result in ugly, brittle code that slows teams down and impedes further change.

Design guided by feedback

Mocks enable isolation.

As Kent Beck framed it, isolation lets us move fast without breaking things… but only when done with intention. We don’t want tests depending on flakey APIs, unfinished features or things that don’t need to exist to verify an object’s behaviour.

This control is powerful. It means we can start shaping contracts before a system is ready. Mocking supports design by encouraging us to think about interfaces, interactions and abstractions based on actual usage not assumptions.

If you require six mocks to test a single behaviour then you are likely missing an abstraction. If a test specifies six interactions against a single mock, then that conversation should likely be simplified into a single, richer call.

Fragility feeds rigidity

Used well, mocks enable insight and clarity. But used poorly, they lock tests to implementation details that break with every refactoring, even when the system continues to work perfectly.

When your tests snapshot structure, developers stop refactoring, the code calcifies, and the team eventually grinds to a halt. Rather than providing confidence, your tests become an inhibitor to change - a liability, even.

If you mock internal methods, return mocks from mocks, mock everything in sight... these are anti-patterns, not arguments against mocking. The problem isn’t the tool; it’s how we use it.

Lost in translation

Part of the problem here is that mocking frameworks blur terminology. In theory:

Stub: “I need this dependency to return predictable data”

Mock: “I need to verify this interaction happened”

Fake: “I need realistic behaviour without real infrastructure”

Spy: “I want to peak at what happened after the fact”.

In practice? Most libraries just say “mock.”

That linguistic drift has consequences. If we can’t talk clearly about what we’re doing, how do we evaluate whether it’s the right approach? Knowing whether you’re simulating behaviour or validating interactions matters - not just for the test, but for how you think about your system’s responsibilities.

If a test fails, you want to know what broke - and why. Misusing mocking terminology can lead to confusion in teams, poor onboarding, and muddled test coverage. Bringing back clearer language around test doubles helps teams be intentional. If you’re faking an in-memory repo, call it a fake. If you're tracking calls, call it a mock. It may feel academic at first, but in growing codebases, precision buys clarity.

The balanced take

In reality, not every dependency needs a test double. Using the real implementation is often simpler and more reliable… an in-memory database for testing repository logic, or the actual email formatting class when testing a notification service. The key question isn't "can I mock this", but "should I"?

Martin Fowler once pointed out that mocks are great for driving design… but terrible if they dominate it. The challenge is finding that middle ground. We don’t need to ban mocks. We just need to be more considered about them.

If you find yourself addicted to mocks and are desperate to break the cycle, start by asking yourself:

What boundaries in our system make sense to mock?

Are our mocks helping us understand behaviour? Or just helping tests pass?

How often do our mocks break due to internal changes, not actual regressions?

Would revisiting mock vs stub vs fake language clarify our thinking?

When mocking hurts, do we blame the test? Or the code it's testing?

Do we have the skills and know-how to tackle these challenges ourselves?